People often ask me what it’s like in Alaska, living here in Fairbanks, a city in Alaska’s Interior on the Chena River. That’s almost impossible to describe. Alaska is more than a place, but a feeling. There simply aren’t words to describe the emotions you have when you see a landscape so majestic and expansive. Even the superlatives can only color around the edges and leave impressions. Alaska is big! How big is it, you ask? The best way to show this is superimposing a map of Alaska on the lower 48, known to Alaskans as “Outside”. In this representation, Alaska stretches from coast to coast and nearly from Canada to Mexico. If Alaska were divided in half, Texas would only be the third-largest state!

What follows is a travelog of first impressions written by me, a Cheechako. Cheechako is an Alaskan expression of a newcomer who hasn’t yet survived a winter and are generally clueless about life here. So, there you have it. I’m a Cheechako on the Chena.

Alaska is more than a place, but a feeling.

I’ve written earlier about why I came to Alaska and how I got here. In my brief time, I traveled by ferry through the Inside Passage, past the quaint towns of Ketchikan, Wrangell, Petersburg and the capital city of Juneau, which is only accessible by ship or air. I’ve been blessed to travel across much of the world and have seen spectacular things, but really nothing compares to the fjords, glaciers, and alpine vistas of the southeastern Alaska coast. Normally a rain-soaked part of the state, I was blessed by fair skies. Every view over every mile could have been a postcard.

Traversing the mountain passes from the southeastern coast of Alaska at Haines through the southwestern Yukon in Canada, I arrived in the Interior, a wide area north of the Wrangell Mountains and Alaska Range and south of the Brooks Range, about the size of Texas.

It’s a land of contrasts: hills and valleys covered by the boreal forests of birch, aspen, willows, and spruces. There are broad flat valleys, or flats, that are dotted by tortuous, braided rivers with oxbow lakes and ponds. Permafrost is a thick layer of permanently frozen ground and it is ubiquitous, growing closer to the surface as you move north. It prevents drainage of waters, creating ponds and lakes with muskeg, raised earthen areas with scrub and spindly black spruce trees that grow there and on the northern flanks of hills.

The white spruce cousins are better nourished and grow taller on the southern slopes. There are massive rivers including the mighty Yukon River, which bisects the Interior. The Interior is a land of extremes. As I write this on July 24, 2023, the high temperature was 87°F. Winter temperatures in some places can drop to -60°F. Sourdoughs, or people who have lived for many years in Alaska, will tell you the extreme cold is not as cold as it used to be and doesn’t last as long as it did even a decade ago.

Global warming is an undeniable fact here.

The thawing of the permafrost (and refreezing in winter) buckles the roads and sometimes fractures them. Summer road work frantically repairs these bumps and heaves, but driving here is often a bouncy affair over the buckles.

Remarkably, there are fewer potholes than you see in places like West Virginia or other eastern states. The frequent freeze, thaw and rain cycles destroy the pavement in Appalachia. The Alaskan Interior tends to freeze early, but stay frozen throughout the winter, which lasts until April or May when “break up” arrives.

Fairbanks- the Interior’s eclectic city.

With around 32,000 people in the town and immediate suburbs, Fairbanks has its own distinct character. Stretched along the winding Chena River, which flows into the larger Tanana River just west of town, Fairbanks lies along a flat plain with wide avenues and pedestrian and bike lanes. It is the largest city north of Anchorage and hub to the vast Interior and the Arctic south of the Brooks Range. Originally a gold mining town (and there are still prosperous mines north of town), it became a boom town during the building of the Alaska Pipeline, which can be visited as it passes just north of town on its way to the harbor at Valdez.

Fairbanks and environs support two major military installations: Fort Wainwright and Eielson Air Force Base. Fort Wainwright was a pivotal post where Soviet pilots received American-made aircraft and other war gear during World War II as part of the Lend Lease program. These aircraft and other war materials would be sent to fight Nazi Germany, thousands of miles away.

Fairbanks is a station in the Iditarod dog race and the western terminus of the Yukon Quest mushing race. The University of Alaska has its attractive flagship campus here, on a high ground. Looking south on most days, you can see the Alaska Range and even Denali on very clear days. Denali is North America’s highest mountain at over 20,000 feet elevation.

But in other ways, it’s a lot like any other town in any other state. There are two Safeway grocery stores, two Fred Meyer’s (“Freddys”), and a Costco. There are strip malls and fast food restaurants. You’d never believe it, but there are over 20 Thai restaurants in Fairbanks, the largest concentration of Thai food in the United States- and it’s excellent!

The Pacific Northwest tradition of drive-through coffee booths is abundant in Fairbanks. They’re everywhere and almost always busy, even into the evening hours. Italian sodas with a shot of half and half are true delights here.

The downtown, such as it is, has some popular spots, including an excellent Moldovan restaurant. The architecture is eclectic- a mix of different architectural styles, from log cabins to brutalist, to others that are reminiscent of post-Soviet structures.

Right now, tourists continue to pile into town for the midnight sun. I’ve been here for two months, and we’ve not had dark night yet, although the daylight hours are becoming rapidly and noticeably shorter.

There are steamboat rides on the Chena, restaurants and hotels along the river, and Pioneer Park, a quasi-open air museum and entertainment area with a salmon bake each night in the summer.

There are real museums, like the outstanding (and free) Morris Thompson Center that focuses on Native Alaskan life in the Interior and the University’s excellent and intriguing Museum of the North, housed in an architecturally stunning building. Hills, which are the beginning of the White Mountains, ring the town to the north and up the Chena River Valley you can find superb hiking and the popular Chena Hot Springs with its Ice Museum. While we’ve not seen bear, we have seen many moose, including some in the backyard.

While Alaska is thousands of miles from Appalachia, there are similarities. We share the same chronic diseases, the same struggles, and people embracing an independent spirit to live on their own terms. There aren’t “hollers” but many prefer living in the woods. Outhouses are common here (which makes me shudder when I think of making trips to the privy in the winter). People are colorful and eclectic here, and so often, though over 3,000 miles away from home, it sometimes feels very familiar.

The Top of the World

My work took me to the most northern city in the Alaska and therefore the United States: Utqiagvik, which was formerly called Barrow and is still called Barrow by many of the inhabitants. The area north of the Brooks Range is called the North Slope, or just “the Slope” by Alaskans. It lies on the tundra, which is a giant sponge in the summer, punctuated with lakes that cluster right until you reach the shore of the Arctic Ocean. This is an area rich with oil and gas, which provides jobs and money for locals, while creating environmental headaches for a delicate landscape and the creatures that depend on the land.

My first impression of Utquigvik was that of Mad Max in the Arctic. It’s barren with no trees for hundreds of miles. Houses and buildings are built on pilings in the shifting tundra, sometimes sinking the houses and stairs in an odd way that reminds me of a Dr. Seuss illustration. Snowmobiles (called snow machines here), 4-wheelers, and other vehicles are found in various states of assembly and disrepair. Everyone drives on the muddy roads on two or four wheels with great speed. Kids are driving 4-wheelers with other kids on the back of the vehicles.

Everything’s relative. In 40°F temperatures, kids are playing in t-shirts.

There are no roads that connect Utqiagvik with the world- only airplanes and barges in summer are able to bring supplies. There’s no service that hauls away broken machinery or appliances. There are no hills or ditches to hide them. Spare parts are precious commodities, and things often weather outside in the elements until they’re fixed. It is a clash of the modern world and its gadgets and a traditional way of life, hunting whales, seals, and walrus for food. It is a place at the intersection of land, sea, sky, and time. This is a culture that not only survived but thrived for over 2000 years in one of the most inhospitable climates imaginable. Their language is different than other Alaskan Natives and their people and related tribes are spread across Alaska, northern Canada, all the way to Greenland.

Their artwork is exquisite, using carvings of ivory from walrus tusks and whale bone, demonstrating a highly evolved culture. The traditional food culture includes every part of every animal they can catch. I tried muktuk, whale blubber and skin. The gray-blue skin was chewy and I can best describe as tasting the way the ocean smells. The layer of fat was not unpleasing and mild. Really, when you think of bacon and lard, it’s not that much different.

I want to return one day to Barrow, just not in the winter. When the sun sets in mid-November, 300 miles north of the Arctic Circle, it rises again only after more than two months.

I came to Alaska to work for an organization that provides healthcare for these original inhabitants of what we call North America. They are a broad network of many cultures that do not conform to modern-day borders.

The Yup’iq people of St. Lawrence Island are related to their Siberian cousins. The Cold War and current tensions artificially divide their kin, a border wall not of concrete or steel, but of ocean, ice, distance, and politics.

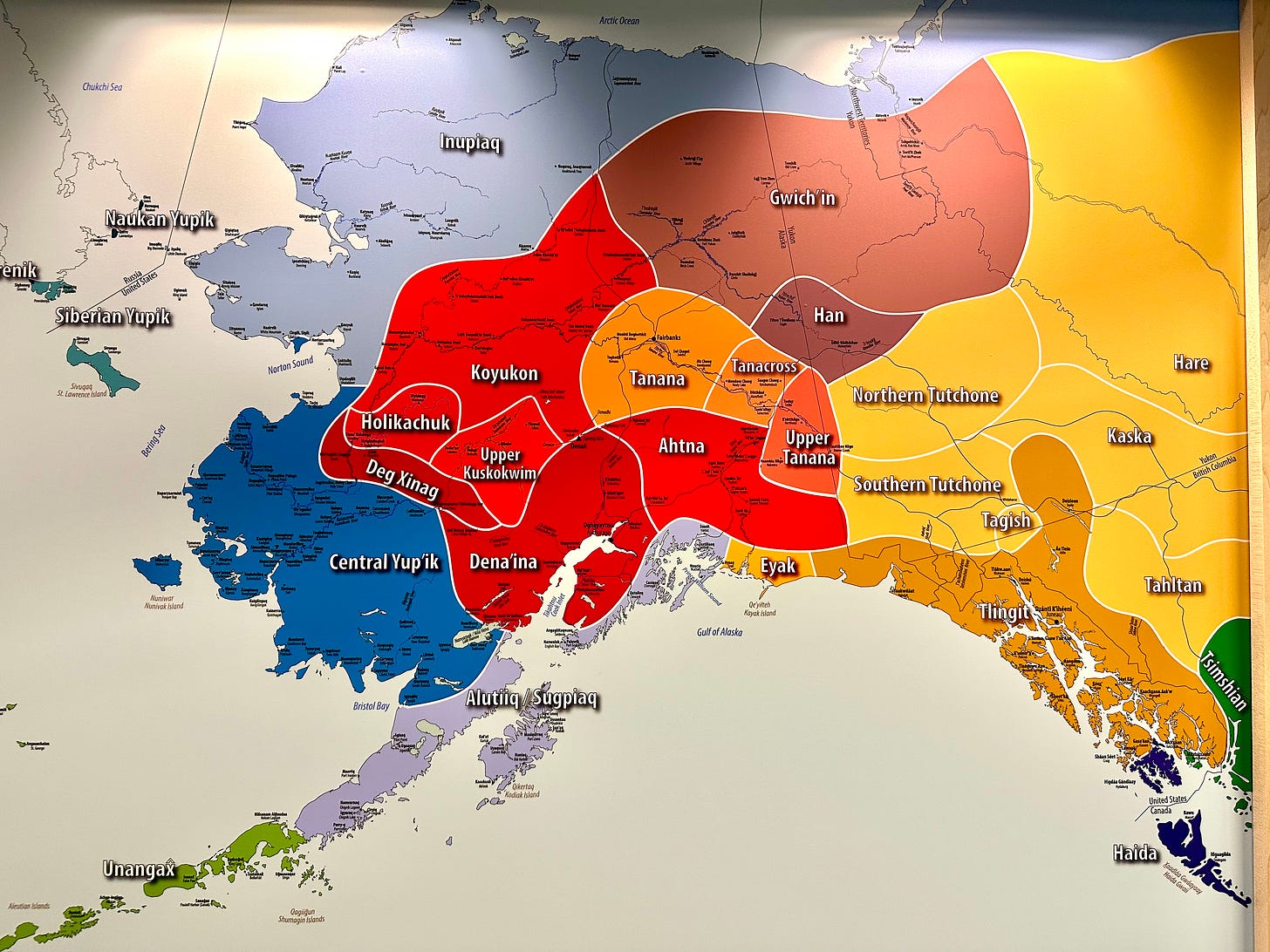

The Gwich’in people are artificially divided by the U.S.- Canadian border. Most people don’t think of Alaska as an ethnically diverse place, but there are almost 230 Federally-recognized tribes with about 180,000 tribal members out of a total population of 731,000 people in Alaska. There are 20 native languages with numerous regional dialects.

To Eskimo or not Eskimo

In my understanding, before arriving to Alaska, the term Eskimo was a pejorative, an insult to Native Alaskans. I was surprised- no, shocked- to hear Inupiaq people refer to themselves as Eskimos! So, I did the Cheechako thing and asked a group of Inupiaq about the use of the term Eskimo. They were proud to be Eskimos and were not insulted when others (white people specifically) called them Eskimos.

An Athabaskan man, who was also sitting in the circle was deeply offended to be labeled as an Eskimo. Athabaskans are ethnically different than other Alaskan Native cultures (and related, believe it or not, to the Navajo and Apache of the Desert Southwest, a story for another day). Even among the broad group of Athabaskans, there are distinct cultures, dialects and tribes.

So, for those of you traveling to Alaska: The problem stems from applying the term Eskimo by colonizers to all Alaskan Native people. It would be like calling a Spaniard a Pole or referring to a Thai as Chinese. The application of the term Eskimo to all Native Alaskans is simply ignorant. If you’re on the Slope, you’re probably safe in using it. Otherwise, it’s just better to use the term Native Alaskan and avoid coming across as a colonizer.

Winter Is Coming

While my brief, light, and pleasant summer in Fairbanks has been a treat, there is a palpable feeling that we are in Winterfell and indeed, Winter Is Coming. The reminders are everywhere. Alaskans in the Interior have the telltale signs on their cars- the plugs that hang out of the grill. All around town, there are stanchions, including at my workplace, with electrical outlets. In the winter months, cars must be plugged in to keep the engine blocks, oil pans, and batteries warm in extreme cold.

At -40°F, rubber gets hard and brittle and tires, flat on the road surface, drive like the Flintstones’ car with irregular wheels. Collisions in extreme cold don’t crumble plastic- it shatters like glass. Everyone is preparing, fixing roads and driveways, completing construction, and doing the chores to prepare for the inevitable cold and dark days. Power outages can happen, and houses can freeze, and water pipes burst. Backup generators are mandatory and mine was just installed- an on-demand generator that runs off a 250-gallon propane tank. My sourdough friend Greg pointed out that propane turns to liquid at -44°F, meaning the gaseous fuel is not able to be used- so a tank warming pad to keep it above that temperature is needed. Another Cheechako lesson.

Cars need to be winterized and repairs completed before the days turn shorter and the snow begins to fall. Nature has its own hourglass- the fireweed plant. As summer progresses, the blossoms open ever higher on the plant. When the top of the fireweed blooms, it heralds the end of summer. In September, as the days shorten and the temperatures plunge, the aspens and birch burst forth in a brief spasm of golden color. Then comes the snow that stays until breakup. When the warmth retreats, the darkness reveals an atmospheric miracle- the aurora borealis, which I have never seen. The downhill ski areas will open, and the cross-country trails and snowshoe paths will open.

I’m looking forward to that.

It was sad to leave West Virginia, the one place I always called home, no matter where I lived. But I’ve long had a love affair with Alaska since I first visited in 2003. I wish more people could see this one-of-a-kind place. The more you see and love something, the more you want to protect it. Alaska is a rugged, unforgiving place, but more fragile than we might think. Both the land and Native peoples have hung on in these most challenging of times. Like the rest of this beautiful country, the land and people deserve our respect and protection. Like West Virginia, Alaska’s land and its people have struggled. Been exploited. But persevered.

Thanks to Kelli Caseman for her insights and editing!

Terrific article! Great detail. I was stationed on Kodiak for a year. Then spent three years covering Alaska while w the Dept. of Justice. Magnificent place to be. Lucky you!

Hi Dr Brumage. Enjoyed this! I was stationed at Ft Wainwright Fairbanks Alaska during winter 2007 while the new army hospital was being built. During that time they had me work at Fairbanks Memorial Hospital taking care of all the military admissions. The hospital was amazing and the people/staff were fabulous. When my time there was over, I was ready to transition out of the army. The hospital offered me a job which I almost accepted. Hope you are also enjoying your time there in Fairbanks.

- Dr Leslee Ball-Scovel